In Iain Banks' Look to Windward (2000; p. 223), a character raises the question of poisoning another, only to be met with the response, "Well, our medicine effectively became perfect about eight thousand years ago..." and so the poisoning in question wouldn’t work because any inflicted disease would be trivial to cure. I liked this throwaway line as a casual reference to the superiority of The Culture in which it exists, but it also causes me to reflect on how we don't describe anything as being “perfect” in our own society.

My background in Art as a discipline means I've thought about it more than the average person for a number of years, and it has struck me for a while now that 'art became perfect' sometime within the last several decades. Perhaps going back to World War II, thus making it a post-war phenomenon, or since the 1960s, when everything seemed to change, or since the 1970s when market forces corrupted it. So how can I write that it was corrupted fifty years ago and yet also claim that it has become perfect?

To clarify right away, I mean art here as a craft and the artist as a maker of things. To say that it has been perfected is to argue that our ability to make things as reached a point of ease and triviality.

Art as visual two-dimensional media has always existed as a decoration. For as long as we’ve been building walls there've been people tasked to make pictures on them. Before then, we were painting on cave walls. Quite often religions have inspired and commissioned art works, and so from ancient Egypt through to Michelangelo, religious illustration was a driving impulse. We're also told that the theatre had its beginning in Greek religious festivals. Fast forward to the 17th Century when Rembrandt and Shakespeare are examples of their crafts; by the 1600s arts are theatre, sculpture & painting/drawing. The Dutch loved to decorate their homes with paintings. In Rome, a lot of ancient statues had been dug out of the ground and inspired the Renaissance a century before.

In the European Renaissance a science of visual representation developed. Perspective and oil paint used by the likes Leonardo da Vinci strove to make what we could call a "handmade photograph" - they elevated craftsmanship as high as they could to faithfully reproduce what they saw. We later learned to use lenses to focus the scene onto a recording surface and shortcut through the required skill, and up until the mass adoption of colour photography, the skill of an artist to reproduce faithfully was valued. For that matter it is still valued because many people recognize how difficult it is to reproduce something by transmitting sight into the hands.

At the beginning of the 20th Century, you had photography as a compliment to painting. And you had the movies as a compliment to theatre. Both nascent forms were seen as lesser experiences, but nevertheless they had their audiences.

By the mid 20th Century, essays had been written about photography as its own artform, and movies had moved past theatre in their capacity to reproduce life's dramas. Walter Benjamin worried about the preservation of an artwork's 'aura' when it could be photographed in grayscale and reproduced widely on paper. Wagner's dream of a Gesamtkunstwerk (‘complete work of art’) had happened through the movies, and the mid-century saw the flourishing of epic dramas like The Ten Commandments (1956) and Ben Hur (1959).

At that time, movies moved into the home as television, and now the hearth was a box showing synchronized sound photographs beamed over radio. Per Marshall McLuhan, the logic of the theatre began to replace the linear logic of literature, so by the 1960s, you had McLuhan channeling Heidegger's phenomenology of Being into "mass media is the extended nervous system". In art galleries you had theatrical set-design being called 'installations' while 'performance artists' did things that would have once happened on a stage.

By the 1970s, art had come to mean: things happening within galleries that include painting, sculpture, installation, and performance art. But the first generation of children raised with televisions thought they could also make short films, and so that too entered the gallery space as 'video art'.

Robert Hughes told the story of what happened next is his last documentary, The Mona Lisa Curse (2008). According to that tale, during the Cold War the Mona Lisa was shipped to New York's Metropolitan Museum for an exhibition in early 1963. People lined up around the block to see it - but then as now, it was about 'standing in the presence of the famous artefact' (basking in Benjamin's aura) rather than seeing a painting. Hughes was disgusted to see a painting attain celebrity status. The world of movies, televisions, and magazines (Hughes was the art critic for Time) had already melted the brains of the citizenry into adherents of the celebrity cult that continues to wreak havoc to this day. As Hughes described it, the painting stopped being a historical art piece produced by a Renaissance Master and was now something to look at like a movie.

I could rephrase this as ‘it stopped being an historical artefact produced by an 16th Century optical scientist’. Reframing Old Master painters as opticians, one could say that as a rudimentary optical scientist Leonardo studied the effect of light and vision and contributed to the history of painting as craft, so that by the end of the 19th Century, painters could be taught how to make "hand painted photographs", complimented by photography, which could replace drawing to capture poses.

The reproductive fidelity at the turn of the 20th Century was so great that other artists sought challenge in taking trains to the countryside to paint outdoors and more roughly, thus creating Impressionism. Which is to say when handmade photographs became easy, the works of human messiness, interpretation and imagination became valued, branching off to Van Gogh and Picasso, whose death was reported in Time magazine in April 1973.

Back to Hughes’ story: after the block buster success of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, New York's art collecting cognoscenti took notice, and while Andy Warhol worked at his Factory using commercial art techniques to mass reproduce images, collectors and dealers began to buy, hodl (sic) and sell. According to Hughes, the lesson the Mona Lisa taught America was that art was adjacent to Hollywood celebrity culture, and it could be bought at a retail street-shop gallery and resold to the wealthy business class at extraordinary amounts through an auction.

So, by the 1990s, when I went to art school, art making and dealing was something that could make you wealthy and elevate you to the aristocratic business class, thus making it "classy". The media frequently featured stories about the Young British Artists patroned by Charles Saatchi. Movies like 9½ Weeks (1986) and TV shows like Sex in the City (1998-2004) depicted the gallery job as glamourous. But Hughes’s narrative of art becoming a part of celebrity culture is the story of its corruption.

At this point there is a belief that art is just a money laundering scheme for tax breaks, because bananas taped to the wall get into the news for the obvious reason that as a cultural artefact it's absurd and worthless, and yet so much unregulated money is being exchanged that it seems obvious that things are shady.

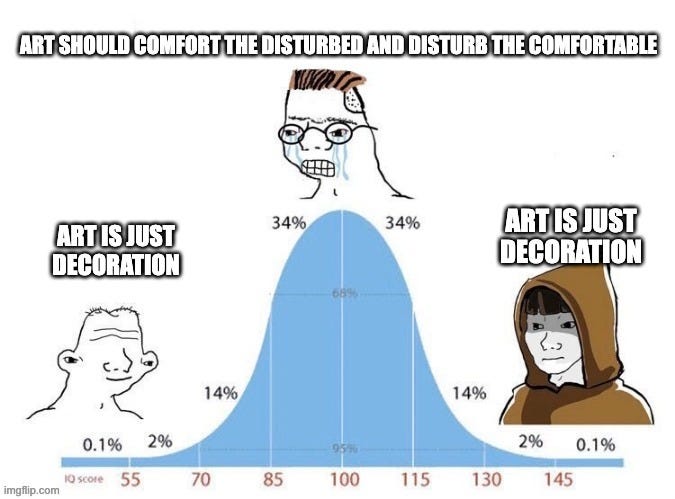

Robert Hughes (1938-2012) was of that generation that considered Art a Humanist discipline akin to literature or philosophy. The ‘curse’ of his documentary title was the expression of dismay in seeing it become another vacuous capitalist commodity, which leads to the cynicism expressed in the tweet/x above.

Once again, how does this narrative equate with the perfection of art? While the intellectual consideration of art as an academic discipline suffers from the same degradation as the other Humanities in our declining culture, our ability to create things has never been greater. Our “technology” has perfected tékhnē.

Hughes asked that art “tell us about the world we live in … art should make us feel more clearly and more intelligently, it should give us coherent sensations that otherwise we would not have had.” It seems to me that Art is doing that, especially in the theatrical forms fragmented into television.

Consider that for hundreds of years, artists illustrated stories from the New Testament, painting after painting of the same scene depicted over and over again over the span of centuries. Consider then how in the 1970s, Franco Zeffirelli made a colour talking movie to be beamed over radio called Jesus of Nazareth, and he was able to reference the history of mass reproduced paintings to compose his scenes. A centuries-long project to illustrate the life of Christ culminated in a TV movie. In one sense, you can say that Christian religious art was perfected in 1977.

Consider again how photography developed over the course of the 20th Century, so that Kodak Brownie cameras first democratized the form, and by the end of the 20th Century everyone had access to colour film photography to record family events. Twenty-five years later, everyone not only has high-fidelity digital cameras on their phones, but video too! The reproduction of sight is now so trivial we don't even think about it, and reproduced images are so prevalent we've created a new form of image-based language through Memes.

Consider that images once reserved for society’s elites and viewable only in ticketed galleries can now be ordered online to hang in your home.

Consider how the trivial creation of digital images has allowed vast databases of image-based binary data, which can now be subject to statistical analysis, so that 'stable diffusion generators' can create quality images on request.

The technology now exists to create any sculpture desired, whether through 3-D printing or by computer aided chiseling.

Art has become perfected in the sense that the creation of works of imagination - the extension of the human mind's idea into the real world of stuff - is now trivial. Some might say that what is conjured up by MidJourney and other AIs can't be art, or is dangerous to the profession, but in turn we can say that MidJourney is serving up suggestions based on a person's inputs, and that the profession has been ‘in danger’ since photography removed necessary skill from the recording of sight over century and half ago. The answer then was that the messiness and imperfection of being human and its impressions began to be expressed, and to this day absolutely disgusting paintings are a poplar genre.

What has always remained valuable is the human imagination behind the creation, to say it’s perfected is like the quote at the beginning: medicine in that sci-fi novel was perfect in that it was robust, available, and trivial to accomplish. Citizens in The Culture didn’t have to worry about disease, because disease was a problem that had been solved. It seems to me that the ability to extend into the real world the figments of our imagination is a problem we solved during the past hundred years.